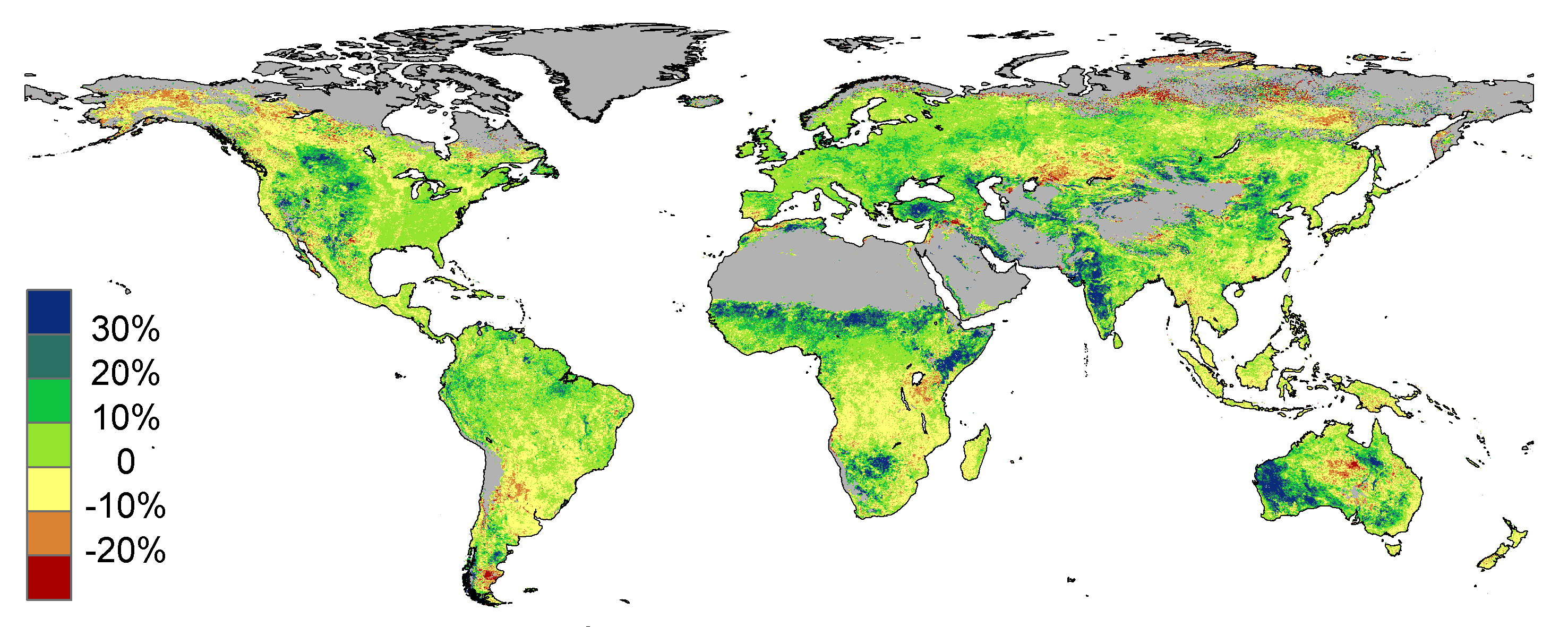

Increased levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) have helped boost green foliage across the world’s arid regions over the past 30 years through a process called CO2 fertilisation, according to CSIRO research.

In findings based on satellite observations, CSIRO, in collaboration with the Australian National University (ANU), found that this CO2 fertilisation correlated with an 11 per cent increase in foliage cover from 1982-2010 across parts of the arid areas studied in Australia, North America, the Middle East and Africa, according to CSIRO research scientist, Dr Randall Donohue.

“In Australia, our native vegetation is superbly adapted to surviving in arid environments and it consequently uses water very efficiently,” Dr Donohue said. “Australian vegetation seems quite sensitive to CO2 fertilisation.

This, along with the vast extents of arid landscapes, means Australia featured prominently in our results.”

“While a CO2 effect on foliage response has long been speculated, until now it has been difficult to demonstrate,” according to Dr Donohue.

“Our work was able to tease-out the CO2 fertilisation effect by using mathematical modelling together with satellite data adjusted to take out the observed effects of other influences such as precipitation, air temperature, the amount of light, and land-use changes.”

CO2 and photosynthesis

The fertilisation effect occurs where elevated CO2 enables a leaf during photosynthesis, the process by which green plants convert sunlight into sugar, to extract more carbon from the air or lose less water to the air, or both.

If elevated CO2 causes the water use of individual leaves to drop, plants in arid environments will respond by increasing their total numbers of leaves. These changes in leaf cover can be detected by satellite, particularly in deserts and savannas where the cover is less complete than in wet locations, according to Dr Donohue.

“On the face of it, elevated CO2 boosting the foliage in dry country is good news and could assist forestry and agriculture in such areas; however there will be secondary effects that are likely to influence water availability, the carbon cycle, fire regimes and biodiversity, for example,” Dr Donohue said.

“Ongoing research is required if we are to fully comprehend the potential extent and severity of such secondary effects.”

This study was published in the US Geophysical Research Letters journal and was funded by CSIRO’s Sustainable Agriculture Flagship, Water for a Healthy Country Flagship, the Australian Research Council and Land & Water Australia.

This article was first published on the CSIRO website HERE

Be the first to comment